| |

|

Unlocking

ARABIC

عربي |

Justin Majzub (ALU ’84) pioneers an innovative design for Arabic letters that turns, swivels and clicks into different forms, allowing learners to discover the language

|

| |

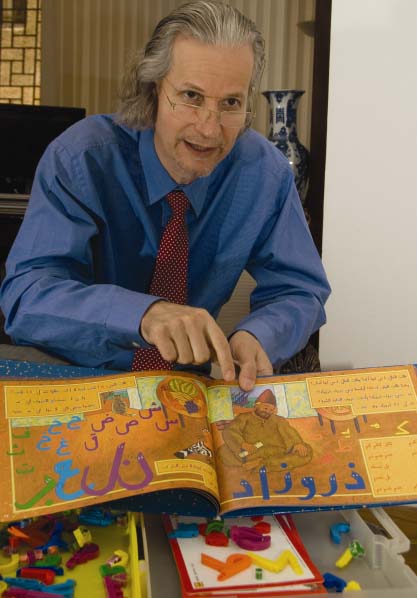

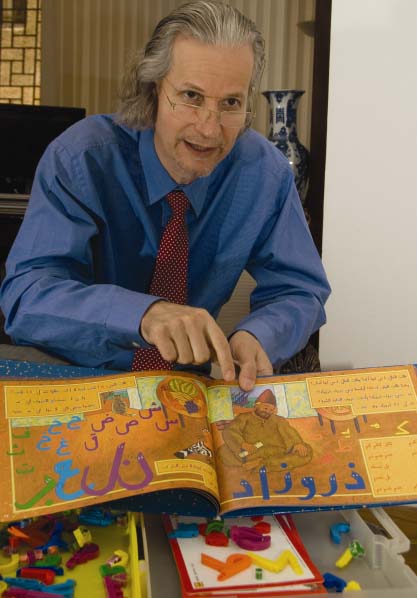

“The Arabic alphabet is notoriously complex, but I think we’ve managed to make it something with which

kids can have a lot of fun,” said Justin Majzub (ALU ’84), whose Abjad Arabic educational system has

changed the way young students in Egypt and the Arab world are studying Arabic.

Abjad consists of an assortment of small plastic magnetized letters that takes up different forms, big wooden letters, writeon and wipe-off picture books, stories, workbooks, coloring books, whiteboards, audio cassettes, puzzles, animal pop-out cards, memory cards, posters, stickers and bilingual CDs of educational games.The whole set makes up a complete Arabic educational system that appeals to children's sense of sight, sound and touch.

|

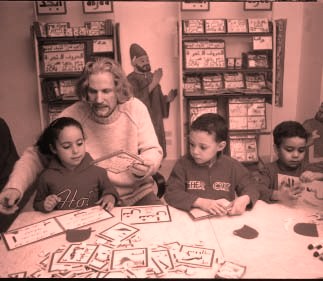

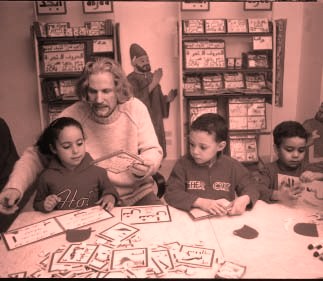

| Story time at the Moroog Nursery |

Majzub is a graduate of AUC’s Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA) and the Arabic Language Institute (ALI). His work began shortly after finishing ALI in the late 1980s.Together with his former Arabic tutor at Oxford University, Majzub wrote a story to help children overcome the main problems associated with learning the Arabic alphabet.The story was produced as a children’s play at London’s King Fahad Academy in 1990, and after several revisions, the story was titled The Prince of the Letters (Amir Al-Huruf), an illustrated picture book.

To make it easier for children, Majzub color coded all Arabic letters into seven groups, or families, based on the seven colors of the rainbow. Letters in the same group have similar characteristics. In his book, letters live together in the letter kingdom, and each is given a distinct personality, such as hah (h), the queen of the letters. |

| |

|

The hamza and vowels become a fun and easy topic with the interactive books, plastic letters and vowel pieces

|

The main problem that Majzub, a British citizen of Iranian descent, was determined to solve was one that he faced when learning Arabic –– that a single letter can take many forms.“In English, a letter always takes up two forms: uppercase and lowercase,” he explained.“You can take a letter and put it on a toy block or on a magnet for the fridge, and these are excellent learning tools. But in Arabic that was nearly impossible because a hah [h] has four different forms: a beginning, middle, end or detached form, which look very different.”

Working alone with a set of woodworking tools, Majzub began personally crafting letters that could turn, swivel and click into numerous positions.“I came up with a way not only to make each letter take the diverse forms needed to write in Arabic, but also to join them together,” he noted, adding that in the book, letters have hands and tails, can hold each other or hold a tail of their own color at the end of a word. Letters without hands cannot hold the following letter in a word.“Through the use of a simple concept such as hands and tails, children understand why some letters join a following letter and why some do not,” Majzub said.

The plastic magnetized letters are the 3D manifestation of the letters illustrated in the book.They have a hinge that allows them to take up different forms, and tactile learners have the opportunity to feel and play with the letters.What was born was more than just a set of magnetized letters; it was an entire curriculum. Majzub spent more than 20 years working with parents, teachers, calligraphers, writers, illustrators, animators, designers, printers,TV personnel, as well as plastic and toy manufacturers, to create what comprises the Abjad system.The consultants came from different parts of the world, including Egypt,Turkey, Iran, Syria, Jordan, Pakistan, India and Malaysia, as well as the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Switzerland, Spain and Germany. In 2001, Majzub moved to Egypt to work more closely with Egyptian schools, teachers and other educationalists on the Abjad system.

|

Today, in Egypt alone, Abjad has been adopted by 200 schools and nurseries, 350 special-education schools, 50 educational centers, 20 adult-education classrooms and approximately 75 top bookstores and toy stores. It is also being used in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan, Syria, Libya and Sudan, as well as the United States, Canada and Europe.“We’re ecstatic about how it has been received,” Majzub said.

Beyond the colorful products,Abjad employs an educational philosophy based on the work of Diane McGuinness, an influential author whose work in literacy is causing a stir in the educational community.“What I found is that while children may be learning enough to pass a literacy exam, they aren’t actually gaining the skills they need to be functioning readers,” Majzub said.“This goes beyond an academic problem. Learning to read is also the key to becoming a well-balanced, self-confident and selfsufficient individual.”

|

| |

|

One of the problems, Majzub explained, is that a standard approach to reading can encourage children to memorize complete words rather than break the word down into its individual sounds.“What you find is that once a child learns 2,000 or so words, their performance decreases rapidly, and this leaves both the child and the teacher at a loss as to what went wrong,” he noted.

In the United States, for example, McGuinness’s research found that if this type of learning is factored into literacy tests, a stunning 43 percent of English-speaking adults would be considered illiterate.“According to this research, about half the people you’ll meet in America can’t read,” Majzub said.“It’s absolutely staggering.”

These statistics inspired Majzub, who had already been working on his Abjad program for more than a decade, to redouble his efforts to combat illiteracy.“Children are being confused because the systems in use now just don’t work,” he said.“They encourage students to parrot words back to teachers, not to actually read.”

Abjad solves this problem by teaching children to read and write Arabic in a systematic approach.“We teach a child in a way that allows them to apply their knowledge to new situations.We don’t ask them to memorize words, but rather we instill them with the tools they need to decode the language,” he explained.

The philosophy behind the Abjad system results in a fully integrated multimedia environment for children. The characters, sounds and colors are repeated throughout Majzub’s many materials, so that the lessons a child learns on the first day of class will be continually reinforced throughout the program.“The key is that we introduce an idea and allow a child to revisit that idea through different media. If you can combine that with a tactile experience, you’ve created a user-friendly environment for the child,” Majzub said.

|

| Majzub helps children use the Abjad system |

The environment is indeed interactive, and Majzub is quick to demonstrate that each of his letters corresponds exactly to the letter painted in his book.“A child can hold up the plastic letter to the book and participate in the experience,” he explained.The book itself draws heavily from Arabic aesthetics.“It was very important that these materials grow out of an Arabic environment. We wanted to give children something indigenous, not just Mickey Mouse in Arabic,” Majzub explained.

This innovative approach to learning is catching the attention of some of Egypt’s leading educators. “There’s a tremendous buzz being generated,” Majzub said.“The program is attracting people who have no outside incentive to come and learn to read Arabic.To me, that says the system works.”

|

| |

By Peter Wieben |

| |

|

|