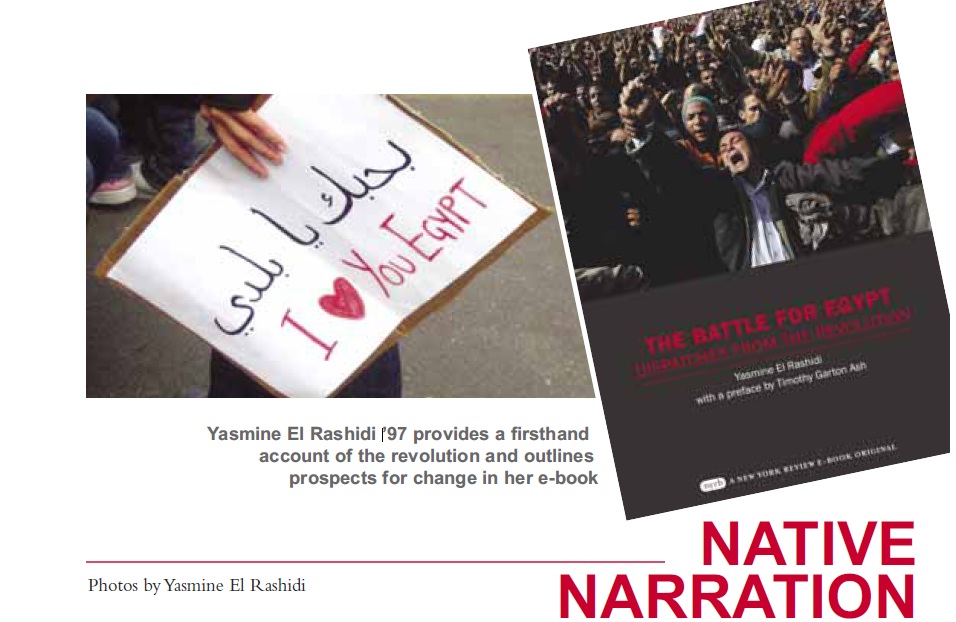

Yasmine El Rashidi '97 is a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books (NYRB), as well as TIME, Aperture

and Bidoun magazines. She has written for numerous publications including

Al Ahram Weekly, The Washington Post and The Chronicle of Higher Education,

and has served for several years as a

staff writer and Middle East

correspondent for The Wall Street

Journal. El Rashidi graduated from

AUC with a bachelor's in journalism

and mass communication, and

attended postgraduate school at

Columbia University's Graduate

School of Journalism. Her newly

released e-book, The Battle for Egypt:

Dispatches from the Revolution (The New

York Review of Books, 2011), chronicles the Egyptian revolution through the

eyes of El Rashidi as a journalist,

writer and Egyptian citizen.

How was it different writing about the revolution? It was the most extraordinary, exhilarating experience of my life. It was also a great hallenge. In journalism school, we are taught to be objective, to keep ourselves out of the story, to maintain balance. In this case, it was particularly hard to do since the event was so intimate to me. I was trying to absorb it as a writer and journalist, but at the same time, I was experiencing it as an Egyptian who was also revolting. This was my revolution too, and my relationship with my country was transforming through it. The personal stakes were really high, so it was certainly different.

In my dispatches to the NYRB, the "I" is very much present. The pieces

were about my own experience, what

I was seeing, hearing, and what was

happening around me.

Did you feel that Egypt was on

the brink of change?

Absolutely. The minute I entered Tahrir

Square at 3 pm on January 25, it was

clear something exceptional was

happening. I had been in Shubra in a

marching protest since the morning,

but it was when I got to Tahrir that my

breath was really taken away. The square

was packed. I had never seen anything

like it before. Then on January 28,

I knew we had hit the tipping point.

That morning, I went to pray at the

Mustafa Mahmoud Mosque with two

friends. I admit I was quite scared. The

phones and Internet had been cut, and

there were state security police, trucks and informants everywhere. I wasn't

sure we would ever make it out of the

mosque. The second the prayer ended,

the chanting began: "Freedom,

Freedom, Freedom, Masr, Masr, Masr!" When we walked out, I was absolutely lost for words. The main street was

already packed with tens of thousands

of people, waving the Egyptian flag,

marching, chanting. I knew at that

point we had broken a barrier of

something. This was the critical mass.

And a few hours later, in a battle on

the bridge heading to Tahrir, you could

see fear being faced and overcome.

The young men at the front lines were

relentless, despite the endless tear gas

being used on us. They kept on

pushing forward. They were willing to

fight, to risk their lives. There was a

moment, crossing Al-Galaa Bridge,

when the riot police fled, and the

young men got up onto the state

security trucks and raised the Egyptian

flag. It was incredible. "On to Tahrir!" they shouted. That moment, I knew we

had already won in a way.

Was there a sense that this was

coming?

I think many of us felt something

beginning to shift before the revolution

started.

Last year was something of a

brutal one for the country, and by the

time the parliamentary elections came

round, which were a sham, it was clear

that something was about to snap. The

parliamentary elections annihilated the

opposition, creating for the

government its greatest ever cohort of

aggrieved politicians. The church

bombing enraged both Copts and

Muslims. The youth activists were

already angry because of Khaled Said

and a million other things, and at a

grass-roots level, people were struggling

to survive. Everyone had had enough,

and by early January, when Tunisia

went up in flames, it was clear we

wanted the same. We were itching to

revolt. You could feel it; it was palpable,

in the air of the city. Tension had been

mounting. The time was close.

Why did you write this book?

I had been writing dispatches for

NYRB, and the publisher, Rea S.

Hederman, decided that it would make

a good book –– as a document, or

testimony, of a time, place and moment

in history.

In your book, you speak about the

strengths and limits of the protest

movement. Describe those.

I think its strength was uniting people,

and, as a movement that was focused

for 18 days, the strength of that focus

was incredible –– it toppled a dictator.

Its limits, right now, are fragmentation,

and at times, an elitist view on some

issues. There are protests every other

day for something. It seems that the

second someone is not happy with

something, they go out and strike. That

is not constructive. We should use the

lesson from Tahrir to mobilize mass

sit-ins, but we need to really think

about what we are asking for. The

backbone of the protest movement

was about survival –– being able to

feed children and support families.

Let's remember what Tahrir, at its core,

was really about.

You also address the prospects for change in your book. What change

do you wish to see in Egypt?

I'd like to see less struggle in the

country. When you go out into the

informal settlements and beyond, it's

heartbreaking. Too large a portion of

the population really suffers, just dayto-day they can barely survive. That

I wish would change. This country is

not poor; we have incredible land

resources that could be developed. It

needs someone with vision, someone

with the interests of the poor in mind,

someone who doesn't think of business

or themselves. For the rest of us, I wish

there was a greater sense of freedom to

be who you want, who you are, who

you need to be. I think back to stories

my grandmother used to tell; it was a

different Egypt. Young women could

walk in the street with short skirts, and

it was okay. Now you are harassed even

if you're covered up. I guess things like

that are luxuries and maybe even at this

point trivialities, but they shouldn't be.

They should be basics. It's all about

liberty, dignity and respect.

How do you see the road ahead?

We have a long way to go; it's not

going to be a smooth transition.

I don't think that it's the end of

clashes, protests, economic woes or

sectarian tensions. In many ways,

I think it may get worse before it gets

better, but in other ways, it is already

better. There is something that

is slowly unfolding, which is

accountability. Within ourselves, there

is also a different sense of ownership,

engagement, connection and pride to

this landscape called home. Something

fundamental has shifted within the

Egyptian psyche. That's invaluable and

shouldn't be forgotten.

By Dalia Al Nimr

|

|

|